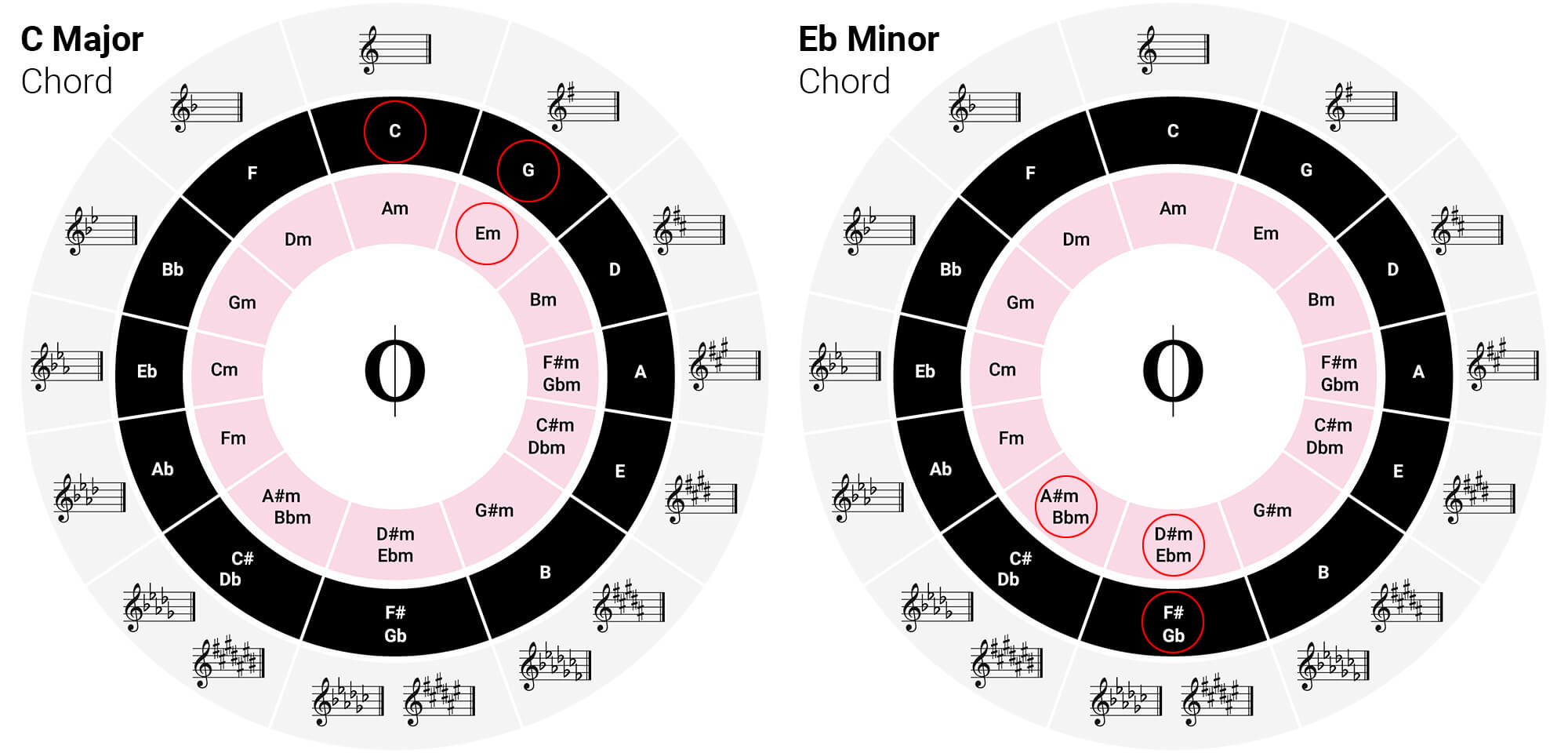

Circle of Fifths: Major and Minor Key Signatures 2 0 1 7, M u si ca l U Images and this PDF document are provided under a Creative Commons BY-SA “Attribution-Sharealike” licence. This means you are free to adapt, reuse and distribute them under the same licence, giving credit and a link to. Figure 1: The Circle of Fifths is a foundational tool in Western music theory. The creation and use of the Circle of Fifths is the very foundation of Western music theory. Along with all the technical things the Circle predicts, it’s also your best friend in the world in. The circle of fifths is a graphical representation of major and minor key signatures and their relationships to each other. The circle of fifths a d e g b c f f c b/a g e/d c g d a e b g/f d/c a e b f major minor moving clockwise around the circle, each key (or in this case, each color) is an ascending fifth from the previous key.

In music theory the Circle of fifths shows how the different keys are related to one another. It is usually shown as a circle with the names of keys around it. If you take any key in the circle, its fifth is the one to its right. It can be easily understood together with a piano keyboard.

Structure[change | change source]

On a piano there are white and black notes (confusingly these are also called “keys”). The white notes are named by the letters A to G of the alphabet. After G comes another A and so on. The black notes go in threes and twos. This makes it easy to see the pattern of white notes. Where there are two black notes together, for example, the white note between them is D. The black notes do not have names of their own. They are named after the white notes next to them. The black note just above (i.e. to the right) of a G is a G sharp. The black note just below (i.e. to the left) of the G is G flat. This means that each black note has two possible names (e.g. G flat or F sharp).

Method[change | change source]

Playing each note in turn, whether a white or a black note, will give a chromatic scale (e.g. C, C sharp, D, E flat, E, F, F sharp, G, A flat, A, B flat, B, C). Each step is called a “semitone” or “half tone”. A “tone” or “whole tone” therefore is a jump of two semitones (C to D, or C sharp to E flat, or E to F sharp).

By playing on white notes from C to the next C we get a major scale. Some of the steps are tones and some are semitones. The semitones come between E and F and between B and C, i.e. between the 3rd and 4th and between the 7th and 8th note of the scale. All major scales have this pattern (tone, tone, semitone, tone, tone, tone, semitone).

Examples[change | change source]

- Starting a scale on a G means that the F has to be an F sharp. This F sharp, the 7th note of the scale, is written in the key signature when writing a piece in the key of G major.

- Starting a scale on a D means that the F and the C have to be F sharp and C sharp.

- Starting a scale on an A means that the F, C and G have to be sharp.

- We can continue like this until all seven notes are sharp (C sharp major).

Each time we went to a sharper key we took the note which was the 5th note of the previous scale (G, with one sharp, was the 5th note of C major. D, with two sharps, was the 5th note of G, etc.).

In a diagram this can be shown as a circle which is called the “Circle of Fifths”. As we get sharper and sharper we go clockwise round the circle.

Flats[change | change source]

The flats work in exactly the opposite way. Instead of going up to the fifth note (e.g. C,D,E,F,G) we can go down a fifth (C,B,A,G,F). F is the scale which has one flat. As we get flatter and flatter we go counter-clockwise round the circle until all seven notes are flattened.

It can be seen that three of the scales each have two possible names: B major (with 5 sharps) can also be thought of as C flat major (with seven flats), F sharp major (with 6 sharps) can also be thought of as G flat major (with 6 flats), and C sharp major (with 7 sharps) can also be thought of as D flat major (with 5 flats).

Minors[change | change source]

Relative minors (the minor scale with the same key signature) can also be worked out by going round three steps of the circle (C major is the relative major of A minor, i.e. it shares the same key signature: nothing). On a keyboard the relative minor can be worked out by going down three semitones (from C go down to B, Bflat, A).

The circle of fifths is the key that unlocks the door to understanding music theory! Take some time each day to study the relationships illustrated the the circle and you'll be playing with the greats in no time.

Circle Of Fifths Poster

What is it?

The circle of fifths is the concept that western music is based on; it illustrates the relationship between scales in a way that is, hopefully, easiest to understand. I compare the idea of the circle of fifths as looking at music theory from a distance; it gives you an overall view of what's going on.

Courtesy of Linkware Graphics

How to Read the Circle of Fifths

How the heck to you read this weird looking chart? Easy there turbo, it's not that hard. Some notes:

- When going clockwise, each key is a fifth above the last; hence 'circle of fifths'.

- When going counter-clockwise, each key is a fourth above the last. Many jazz chord progressions are based off of this pattern.

- In this version of the circle, as well as many others, the uppercase letters represent major keys and the lowercase letters represent their relative minor keys.

- Notice how, starting at C major, one sharp is added to each key as you go clockwise until around C# major; then it switches to flats that decrease by one on each key as you complete the circle. This is why we have sharps & flats. If the sharps continued past C# we would end up with 11 sharps! But when the flats take over they ease the load until the circle restarts.

- Keys that are directly across from one another are tri-tones of each other. ie: C -> F#

Making Chord Progressions From the Circle of Fifths

Remember this common chord progression?

I - IV - V - I

It's an example of subdominant (IV) and dominant (V) chords leading back to the tonic (I). If we have a tonic note we can use the circle of fifths to give us the subdominant and dominant chord of that key. Just locate the tonic in the circle, let's use C as an example, then locate the keys immediately adjacent on each side. So, if we're using C as the tonic the subdominant would be F, immediately counter-clockwise, and the dominant would be G, immediately clockwise.

Circle Of Fifths Chart

Patterns like that are what make the circle of fifths interesting. Not only does it make it easy to figure out chord progressions in any key it also creates a blank canvas for you to come up with your own chord progressions by experimenting with different patterns. Many musical styles are determined by the shape in which the chord progressions make on the circle of fifths. For instance, if you draw an equilateral triangle with each point pointing to a chord you'll get a progression where the chords are all a major third apart.